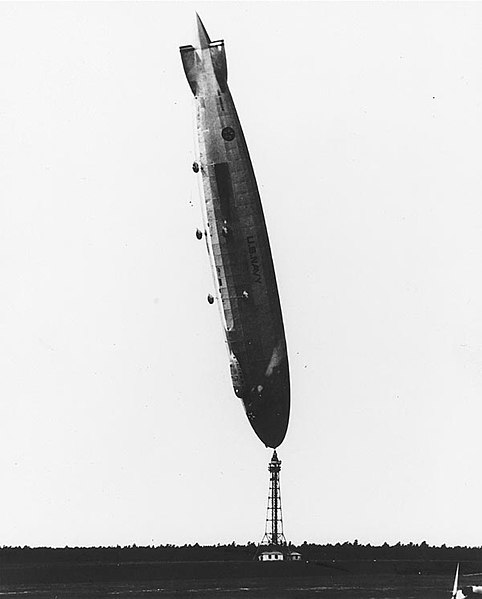

The craft flew the next day in a training evolution. It suffered almost no damage.

Interestingly, this is a craft built in Germany as part of WWI war reparations. The US was awarded operational airships of the German fleet but the crews sabotaged them. This particular airship was a newly built craft in 1924 as a consequence of the United States being deprived of awarded war treasure.

I write today of the unbalanced: those concepts we include in our stories which seem completely out of line.

A civilian involved in a murder investigation?

A boy adrift in a boat with a tiger?

Dinosaurs? Really?

A competition to the death involving children?

When you writers assemble the machinations of your plot devices, they really don't stand critical inspection. At some time in your writing career, you'll reflect on this non-sequitur and considering changing the premise. Maybe you'll reach this point because of an off-handed conversation with a friend.

"What's it about?"

"It's about a boy who turns a shade of purple."

"Why?"

"Because he's different."

"But why? Why does he turn purple and why doesn't he turn back."

Then, we're at it. Why does the character remain purple? We've never seen any who was purple - well, who was to live for long, anyway. So, maybe the purple boy is a stupid idea. It isn't realistic anyway.

We don't want to write one of those books that might be classed with those about magic flying wombats. No one takes that sort of thing seriously.

No one wins Man Booker for anything so extraordinary. It just isn't serious literature. Except for The Life of Pi. Surely that was just an anomaly.

The point is: anything you think of won't stand close scrutiny as just an elevator pitch. It won't stand that scrutiny until you write, re-write, hone, and come to love the characters, concept and execution. Then, that elevator speech becomes a confession of investment, love, and confidence.

"It's about a boy who is fundamentally different from everyone else on the planet, how he learns to use his condition as a statement of his existence, and how his ultimate confidence transforms those who hate him for his difference into allies and admirers."

Purple didn't matter. Different mattered. You'll think that when you watch Hopkins thank the academy from his role in the film adaptation.

Write it. Literature isn't life. Literature is life in a mirror of your choosing.

Put the bones in a box. Let the dog talk. Put the fifteen year-old girl at the murder scene and walk us through her deductive reasoning which solves the crime the police believe to be a freak event.

You don't have to explain "balance" in the concept to anyone. Not. Even. You.

Write it well and the concept's surface absurdity won't matter. Your palette is the human condition. The contrivance of circumstance you use to stage the backdrop for the story is merely that: a contrivance.

Don't examine the raw concept for balance. It's as immaterial as a boy wizard.

Write something that might fall off its axis if you explain it to your father-in-law. I will.

No comments:

Post a Comment